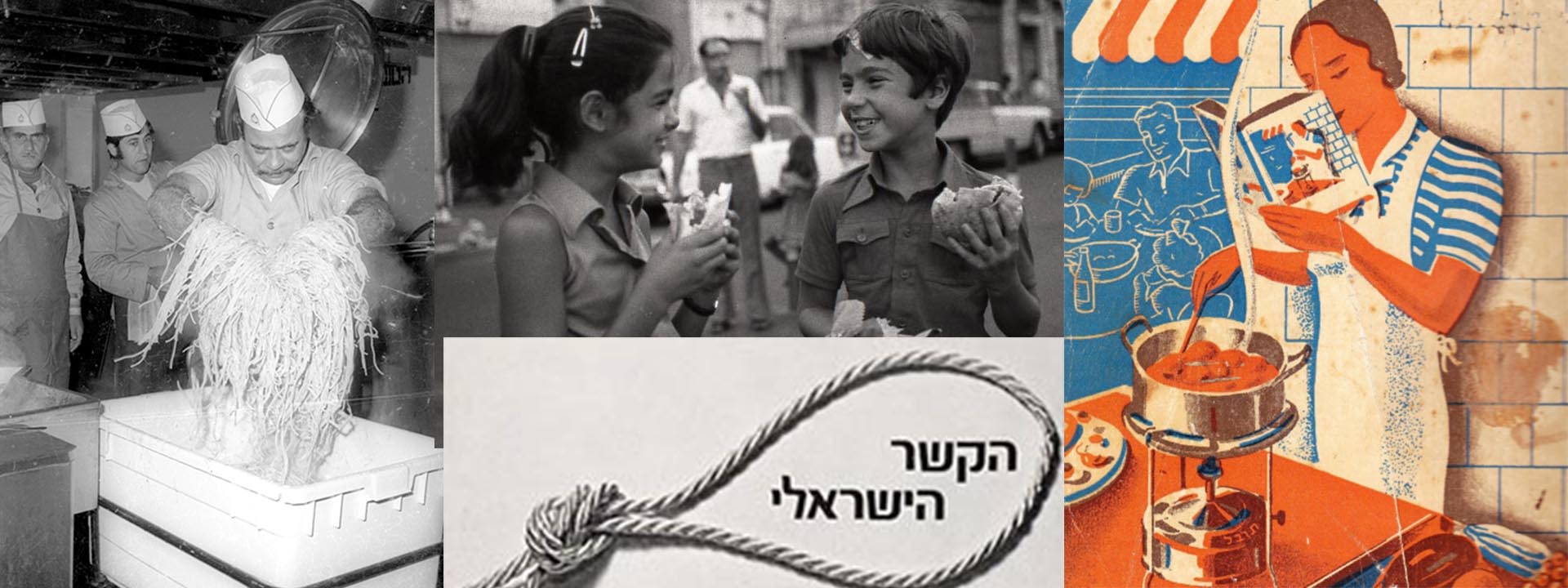

Book jacket of How to Cook in the Land of Israel (Hebrew) By Orna Meir, with Malka Sapir, 1937

“Cuisine” can be defined as a collection of cooking styles, techniques, ingredients and taste preferences that result in dishes identified with a community of people who, over time, recognize these as worthy of being served at their tables. A cuisine is shaped by the historical and cultural conditions of a place and period, and as a cultural phenomenon it obeys symbolic laws that give meaning to regional meals and dishes. Here we will discuss the cuisine that was cooked and eaten on a regular basis in the Land of Israel and in the State of Israel by the local Jewish residents from the 1930s until the early 1960s.

Israeli society was and is still a society of immigrants. Every immigration wave brings with it habits, memories and culinary preferences. However, the major demographic changes that occurred following the State of Israel’s establishment, both in the size of the population and its culinary culture, necessitate distinguishing between the pre-1950s period and the post-1950s period.

A recipe for "Liver-Flavored Eggplant Salad", from Kach Nevashel: Sefer HaBishul (Hebrew) / compiled by WIZO Staff Members, 1964/5

All the Zionist immigration waves brought with them culinary cultures that differed from the local traditions of the Palestinian Arabs, as well as the traditions of the Sephardic Jews who were already living in the Land of Israel.

In the immigration waves prior to 1948, immigrants came mainly from eastern and central Europe. Their cuisines were not homogenous: the “Galitzianer” cuisine was not like that of the “Litvaks,” and these were different from the cuisines of immigrants from central Europe. Despite these differences, the cuisine of the European-Jewish immigrants of this period can be categorized as “Ashkenazi cuisine”, since they all shared similar customs, ingredients and dishes as well as Jewish dietary rules.

In the homes of the Ashkenazi immigrants in the Land of Israel the cuisine that emerged—“Ashkenazi-Israeli cuisine”—was certainly different from that of their birth countries, mainly in the composition of the ingredients, but it still largely retained many typical characteristics. The well-known dish “liver-flavored eggplant salad“ (the recipe can be found in the cookbook: Kach Nevashel, 1952) is an example of how cooks, in this case WIZO staff members, tried to adapt local ingredients to a taste palate familiar to new arrivals from Eastern Europe—especially during the period of food rationing and shortages in the 1950s.

The eggplant was new to the immigrants from eastern and central Europe. Nutritionists and cookbook authors sought to teach homemakers how to incorporate unfamiliar vegetables (tomatoes and zucchinis were also new to many of the immigrants) into the family diet, not only because it was rich in vitamins, but also because it was locally grown and therefore easily available. In adapting a well-known dish from the Ashkenazi kitchen—chopped liver—to the contemporaneous conditions in the country (food shortages and the high price of meat during the austerity period, and on the other hand, the availability of local produce), WIZO sought to help local households serve a familiar and healthy dish that used locally and readily available products.

The immigrants had no choice but to adopt ingredients from the local market that were not part of their prior cuisines; some foods were practically unknown to the new arrivals, such as tomatoes, zucchini and eggplant, and some had simply not been part of their previous diet, such as olives. New dishes were also created from the array of local ingredients, some adopted from Arab cuisine (such as “finely chopped vegetable salad”). However, not every local ingredient made its way into the kitchen. Legumes, for example, were not high on the shopping list.

On the other hand, the local market enabled broad consumption of ingredients that had been considered foods only for the wealthy back in eastern and central Europe, such as eggs, white bread and oranges. As fresh vegetables—tomatoes, cucumbers, scallions, lettuce and radishes—became a regular part of the menu with the enthusiastic encouragement of the dieticians of the day, eating boiled vegetables, such as carrots, beets and beans fell out of favor. The use of seasonings remained limited to parsley and dill. The main meal of the day (eaten at midday) was expected to include meat, and the potato, which had been an important component of the meal in Europe, retained its status, despite the high price. Coffee began to replace tea, which had been the more common hot beverage in Eastern European.

"You too can serve your guests delicious, nutritious 'Telma' hummus"

An ad for Telma Hummus – "The National Israeli Food". Maariv, December 31, 1958.

In the contemporary culinary discourse, the concept of “Mizrahi” or “Middle Eastern” food was identified with the cuisine served in “Mizrahi Restaurants" that first became common in those years—these were the restaurants that Israelis typically frequented on the rare occasions they dined outside their homes. These restaurants served dishes from Palestinian cuisine, mainly grilled meat dishes, and this was where Israelis learned to eat and appreciate hummus. For many vatikim ("veteran" Israelis), whose roots in the country went back to earlier immigration waves (from the late 19th and early 20th centuries), Palestinian cuisine was a sensible source from which to adopt foods for the emerging national Israeli cuisine, because the Arab menu was seen as representing locality, authenticity, and natural consumption of regional, as well as healthy products.

From the 1930s to the 1950s, immigrants from eastern and central Europe were the lion’s share of the Jewish population in Palestine, but after the establishment of the state and the great influx of immigrants from Islamic countries in the 1950s, their relative share decreased.

The cuisines that the immigrants from Arab countries brought with them were very different from those of the local Ashkenazi community, and they were also extremely diverse; Iraqi Jewish cuisine was not the same as Moroccan Jewish cuisine, which in turn differed from the Egyptian. As in other areas of life, the cultural distinction (which had a discriminatory element) between “Mizrahim,” Jews of Middle Eastern origin, and “Ashkenazim”, led to the cuisines of all immigrants from Islamic countries being labeled “Mizrahi cuisine,” while the Ashkenazi-Israeli cuisine was perceived as “Israeli.” Since the Jewish dietary laws were observed in the majority of consumer circles, and therefore also in most homes, and despite the differences and sometimes even the rejection of culinary worlds that had come together in Israel in the 1950s, they could all dine at each other’s tables.

As in the previous waves of immigration, the immigrants from Arab countries sought to preserve their culinary culture even under the prevailing austerity conditions. Like immigrants before them, they too had to adapt to the new reality. They preserved their original cuisine by adapting the dishes to what was available in the local market and especially by the use of spices. This is how Rina Ben Simhon, author of the book Moroccan Food (1982), describes dealing with the harsh reality she faced in Israel:

“...but when we immigrated in 1947, there was a shortage. It became worse during the austerity period. But there was always a holiday in the Moroccan immigrant kitchen. Flour helps to keep up a large part of the cuisine: couscous, mofletta, haringo, sfinge, massapan and dozens of other dishes.”

An army cook preparing spaghetti in an army camp, 1977, the Dan Hadani Archive

Since the Ashkenazi-Israeli cuisine was the cuisine of the hegemony, it was the dominant cuisine found in public and institutional kitchens and discourse. This was the case in meetings of immigrants with nutrition counselors; at food exhibitions for housewives presented by women’s organizations; in immigrant educational youth clubs; in the school curriculum; in government sponsored cookbooks and publications. Ashkenazi cuisine was served to all the immigrants in the Ma'abarot, the transit camps which served as temporary housing for new arrivals. It was served to all children at school meals and to all those enlisting in the army (except the Druze). Official recipes provided to IDF cooks, which followed universal nutritional guidelines, offered dishes from the Ashkenazi kitchen almost exclusively, including tzimmes, goulash and cured fish to name a few. This was the case until the 1980s.

In light of all the above, it seems that it isn’t really possible to point to “the emergence of an Israeli cuisine” in the period between the 1930s and the 1960s, certainly not of a cuisine that was accepted by the majority of the country’s citizens. Nevertheless, it is possible to note a growing trend during the years that followed. While the Ashkenazi menu was an institutional given, dishes and flavors that characterized the cuisines of the immigrants from Arab countries gained new adherents, as did dishes from Palestinian cuisine. As evidenced by the title of an article in the army magazine BaMahane from the early 2000s: “Ashkenazim – we are fed up with you: tzimmes is out, malawah is in, goulash gives way to chraime, couscous replaces petitim, cured fish is off the table and in its place are hummus and tahini. The new army mess is redder, spicier, and more Mizrahi” (Levi: 2003, 7).