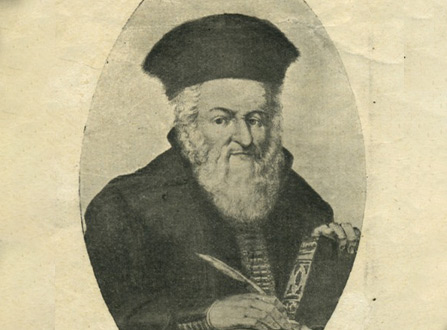

The Vilna Gaon

Rabbi Eliyahu ben Shlomo Zalman, known as the Vilna Gaon, the GRA (acronym for Gaon Rabbi Eliyahu), and even just “the Gaon,” is considered one of the most important rabbis in Jewish history, and Gadol HaAḥronim ("the greatest of the last [of the great sages]"). Though he lived in the period of the “last” sages, who were active from the sixteenth century, some halakhic adjudicators likened his halakhic status to that of the “Rishonim” (lit. "the first [sages]"), who were active five hundred years earlier. In contrast to most of the Aḥronim, The Vilna Gaon did not hesitate to disagree with the Rishonim.

Although he did not hold an official rabbinical position, his influence on halakhic rulings and interpretations of rabbinic, halakhic and Kabbalistic writing is felt to this day. He is considered the father of the stream of Lithuanian Kabbalah, and left his mark especially on the world of the Lithuanian yeshiva. The Vilna Gaon is remembered as the one who led the strongest opposition to the fledgling Hasidic movement. Despite attempts to depict him as an early forerunner of Zionism, academic research does not accept this line of thinking.

The Vilna Gaon was born in Lithuania in April 1720 and died at the age of 77. Already as a small child, the Gaon was considered a prodigy and delivered a sermon in his local synagogue. He was well versed in rabbinic and Kabbalistic literature, and engaged in Torah study all his life while his wife supported the family. He slept little and had only a handful of close disciples. The most famous disciple was Rabbi Chaim of Volozhin, who after the Gaon’s death, founded the Volozhin Yeshiva (considered the “jewel” of the Lithuanian yeshivas).

The Path of the Vilna Gaon

The Vilna Gaon advocated study of the pshat, the literal meaning of the text, and was opposed to the pilpul method of digressive debate. He also dealt with textual corrections of rabbinic literature and the Zohar. His halakhic rulings, considered original and bold, were often in opposition to the views of the Rishonim, the rules of the Shulḥan Arukh, or accepted custom. His rulings were collected by his disciple Rabbi Chaim in the book Ma’aseh Rav, and greatly influenced the customs of the Lithuanian yeshivas. Besides Torah study, the Vilna Gaon also studied the natural sciences and mathematics, which he considered important for understanding the Torah. He even wrote a book on mathematics and astronomy.

The GRA attempted to immigrate to the Land of Israel, but did not succeed and returned to Vilna. At the beginning of the 19th century, under the leadership of Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Shklov, disciples of the GRA began to make their way to what was then Ottoman Palestine, settling first in Safed and later also in Jerusalem. They renewed and maintained the existing Ashkenazi communities, and introduced a new type of separate community, calling themselves Perushim (lit. separatists), that continues to this day. In the middle of the 20th century, the book Kol HaTor, was published which supposedly contained the Zionist-messianic teachings the GRA passed down to his disciples. Today, however, the academic community does not accept the book’s attribution to the Vilna Gaon’s disciples or the authenticity of the viewpoint as representing the GRA’s thinking on the matter.

The National Library has collected a variety of items that shed light on the history, activity, personality and long-standing influence of the Vilna Gaon. The Library contains collections of his commentaries, books and studies written about him, as well as postcards and pictures featuring his portrait.